Geo-blocking game sales

Geo-blocking limits the ability to buy products and services based on the customer’s nationality or residence. The conditions for access to goods and services and payment terms vary according to geographical criteria. In principle, such practices are prohibited in the EU. Does this ban also apply to video games?

The Geo-blocking Regulation1 has been in force in the EU since 2018. In short, it prohibits the use of three mechanisms:

- Blocking or limiting access or automatically redirecting the user to another version of an online interface2

- Different conditions for the sale of goods or services3

- Different payment conditions based on the buyer’s location or nationality.

For example, a seller cannot:

- Redirect a customer to the Polish version of a website when the customer wants to access, say, the Spanish site, just because the customer’s IP address points to Warsaw

- Vary the net price of a product depending on whether it is purchased by an entity from the country of the seller or from abroad

- Require that a buyer whose payment account is located in a different country than the seller’s account pay for the transaction only by credit card.

Does the prohibition of geo-blocking apply to game sales?

Regulation 2018/302 applies wherever it is not expressly excluded. There are two types of exemptions4:

- Industry exemptions, under which the Geo-blocking Regulation does not apply to a given type of activity

- Encompassing a specific ban, so that although the seller must comply with the regulation when conducting business in a particular industry, in certain defined cases a given ban will not apply to the seller.

It is worth considering one or more of these types of exemptions can be applied to the sale of games.

However, it should be noted that even if a specific practice is not prohibited under the regulation (as it falls under one of the exemptions), it may be prohibited under other regulations, e.g. competition law.

- Industry exemptions

There are several industry exemptions, but from the point of view of the video game industry, one may potentially be applicable: the regulation does not apply to “audiovisual services, including cinematographic services, whatever their mode of production, distribution and transmission, and radio broadcasting.” To answer the question whether this exemption applies to the sale of games, it is necessary to determine whether a computer game constitutes an audiovisual service.

There is no definition of audiovisual service in Regulation 2018/302. However, the European Games Developer Federation has advocated treating video games as audiovisual services, issuing a statement entitled “Europe is not ready for the end of geo-blocking of digital games” in which it asserted: “As games are both audiovisual services and copyright-protected works, they are excluded from the scope of the current geoblocking regulation.”5 Such an interpretation would mean that the sale of video games falls under the industry exemption, therefore Regulation 2018/302 does not apply, and, as a result, the game industry is not subject to the bans set out in the regulation.

But taking into consideration the preamble of the regulation and explanations from the European Commission regarding its application, it should be considered that providing access to or selling games, which include visual and sound effects, is not an audiovisual service within the meaning of the Geo-blocking Regulation. Audiovisual services consist primarily of providing access to films (streaming or VoD services) and live broadcasts of sports events. This means that the exclusion of audiovisual services from the scope of application of the regulation does not cover the sale of games. Therefore, in principle, the Geo-blocking Regulation applies to the sale of games, as it does not fall under the industry exemption. In that case, it should be verified whether all forms of geo-blocking as defined in the regulation are prohibited for the sale of games, or there are any exemptions in this regard.

- Exclusion of one of the bans

From the point of view of the sale of games, the exemption referred to in Art. 4(1)(b) of the regulation is relevant. Pursuant to this provision, the ban on applying different conditions of sale of electronically supplied services6 does not apply if the main feature of the services is the provision of access to and use of copyright-protected works, including selling them in an intangible form. This means that the regulation does not ban the change of conditions for the purchase of access to online games (browser games or digital distribution platforms) or the sale of downloadable games based on the origin or residence of the buyer. However, this exemption only applies to online and downloadable games; it does not apply to the sale of games on physical media.

The other two bans, i.e. limiting access to interfaces and discrimination on payment terms, apply in all cases, including when providing access to online games and the sale of downloadable games7 as well as games on physical media (e.g. CDs or DVDs). There are no exceptions in this respect.

It is complicated. The scope of application of Regulation 2018/302 in relation to the provision and sale of games via internet is presented in the table below:

The Geo-blocking Regulation may be amended, and in the near future the exemption described above may be removed. Indeed, the regulation itself requires the European Commission to carry out periodic reviews of how the regulation is applied in practice, the first of which took place in 2020. That review found that it was too early to amend the regulation,8 but the Commission is due to look at it again in 2022.

The regulation does not provide for sanctions for violations. It is up to the member states of the European Union to designate bodies enforcing the regulation and to adopt provisions specifying measures to be applied in the event of unauthorised geo-blocking. In Poland, this is the responsibility of the president of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK), and the penalties the competition regulator may impose are set forth in the Competition and Consumer Protection Act.

Having considered the scope of application of the regulation to the sale of games, a fundamental question arises: Is anything not prohibited by the regulation always permitted? Not necessarily. To understand this better, let’s take a look at the Steam platform case.

What were the owner of the Steam platform and game publishers fined for?

Proceedings by the European Commission against Valve (owner of the Steam platform) and five PC game publishers9 have reverberated strongly in the game industry.

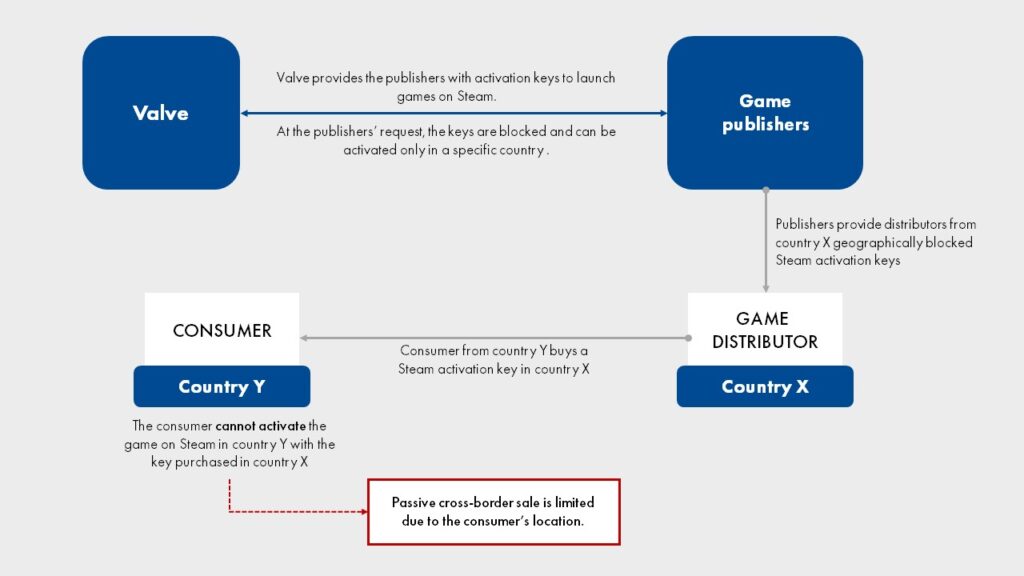

At the beginning of 2021, the Commission announced fines totalling EUR 7.8 million against Valve and game publishers Bandai Namco, Capcom, Focus Home, Koch Media and ZeniMax. As of publication of this article, the decisions in these cases have yet to be made publicly available.10 However, based on the official communication from the Commission and press releases, the reason for the fines was the violation of EU rules on unauthorised anti-competitive agreements that consisted of geo-blocking and led to a restriction of cross-border sales of about 100 PC video games. According to the Commission, the prohibited geo-blocking took two forms.

First, Valve provided publishers with activation keys allowing the operation of games purchased outside of Steam (in digital form and on physical media) on the platform, with the keys geo-blocked by Valve at the request of the publishers to allow the game to be launched only in a specific territory. As a consequence, a buyer of a game with a geographically blocked key could activate it only in a specific EU member state. The key did not allow the game to be launched on Steam in another location. These practices lasted from September 2010 to October 2015.

Second, the Commission fined four of the five publishers (Bandai, Focus Home, Koch Media and ZeniMax) for entering into licensing or distribution agreements with distributors other than Valve which contained clauses restricting cross-border passive sales11 of PC games within the European Economic Area. Depending on the publisher, these practices lasted from 3 to 11 years, between March 2007 and November 2018.

According to the Commission, the scheme worked as shown in the following graphic:12

The game publishers cooperated with the Commission (including by providing evidence in the case), which resulted in a reduction of their fines by 10–15%. The fine for Valve, which reportedly did not cooperate with the Commission, was not reduced.

In a statement for the Eurogamer website, a Valve spokesman said that Valve had cooperated with the Commission but did not admit to breaking the law, as it disagreed with the findings and the penalty. Because the sales of geo-blocked activation keys took place outside of the Steam platform, Valve claimed there was no basis for imposing liability on the platform owner. The geo-blocking of keys was disabled in 2015, except for cases where such a mechanism was necessary due to local legal requirements or game distribution licence restrictions.

Summary

The Geo-blocking Regulation largely applies to sales of video games. Therefore, in principle, it is not allowed to restrict access to the game interface or to apply different terms of sale and payment for games on the basis of geographic factors. The only exemption in this respect (albeit an extremely important one, as it concerns the greater part of the gaming market)13 is that the regulation does not prohibit the geo-differentiation of terms of sale of downloadable games or access to online games. All bans set out in the regulation apply to the sale of games on physical media.

It is important to underline that certain activities related to geo-blocking in the game market, although not falling under the regulation, may violate other regulations, in particular competition law, as evidenced by the case of Steam and the five game publishers. Therefore, to avoid exposure to severe fines from competition authorities, platform owners, and distributors and publishers of video games, should carefully examine the conditions for licensing and distributing products in the European Union, in particular any restrictions in this respect. Agreements restricting access to goods or services may be found to restrict competition or infringe the collective interests of consumers.

Paulina Mleczak

1 Regulation (EU) 2018/302 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 February 2018 on addressing unjustified geo-blocking and other forms of discrimination based on customers’ nationality, place of residence or place of establishment within the internal market and amending Regulations (EC) No 2006/2004 and (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive 2009/22/EC.

2 An online interface is not just a website but all kind of software and applications, including mobile applications.

3 This ban does not prevent the offering of different conditions, including prices, which differ from one EU country to another or within a single country, to customers within a particular territory or targeted at particular groups of customers in a non-discriminatory manner.

4 This article does not discuss the use of practices prohibited by Regulation 2018/302 when required by a specific provision of EU or national law (Art. 3(3) and 4(5) of the regulation) or the exemption in Art. 4(4) of the regulation (entities exempt from VAT under Chapter 1 of Title XII of Directive 2006/112/EC).

5 European Games Developer Federation, “Europe is not ready for the end of geo-blocking of digital games.”

6 According to the regulation, these are services provided via internet or an electronic network, the provision of which, due to their nature, is essentially automated and requires minimal human intervention, and is not possible without recourse to information technology.

7 This is also confirmed in the European Commission’s FAQs on the Geo-blocking Regulation.

8 The 2020 review by the European Commission found as follows:

- Demand for cross-border access to games and software appears to be low.

- Distribution practices are mainly based on geographically unlimited and non-exclusive licences.

- Extension of the scope of Regulation 2018/302 to include the sales of online games would likely result in:

- Increasing the variety of items available in individual catalogues (however, gaps in availability apply mainly to titles with relatively low demand or ratings)

- Reduction of the price of games (although the differences within the European Union are small) and an increase in their sales, with the increase in sales not compensating suppliers for the full price reduction, meaning that it would be associated with a reduction in revenue for developers/publishers

- Overall impact on consumers and suppliers could be slightly positive, at least in the short-term perspective. The negative impact could be greater for smaller or domestic PC game distributors with a weaker market position but higher operating costs for cross-border sales.

(Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the first short-term review of the Geo-blocking Regulation, {SWD(2020) 294 final}, COM(2020) 766 final, 30 November 2020).

9 Press releases: Commission opens three investigations; Commission sends Statements of Objections to Valve and five videogame publishers; Commission fines Valve and five publishers of PC video games.

10 Press releases and short notes have been published stating that the Commission and the fined companies are in the process of drafting versions of the decision not containing confidential information. See information on the Commission website.

11 This is a concept of competition law. Active sales involves making contact with customers, e.g. by sending unsolicited emails. Passive sales are made in response to unsolicited inquiries from individual customers. A distributor’s use of a website is considered to be a form of passive selling. For more, see points 51–52 of the European Commission Guidelines on Vertical Restraints.

12 Graphic adapted from the communication from the European Commission.

13 According to the Statista website, in 2018, 83% of all computer and video games in the United States were sold in digital form and only 17% on a physical medium. It seems reasonable to assume that in other parts of the world, or at least in Europe, the share of digital games in relation to those sold on physical media is similar. Moreover, during the pandemic, interest in digital distribution of games has undoubtedly grown.