Fundamental issues a game developer should pay attention to when negotiating a contract for publication of a video game

Contracts for publication of video games are concluded between game developers and companies specialising in publishing games (sometimes referred to “dev-publisher agreements”).

Just a few years ago, the word in the

video game industry was that the role of publishers in the process of

commercialising new games was on the way out, and the future of the industry

was in self-publishing of games by developers. But publishers have not gone

away, and still represent a hugely important element of the operation of the

entire industry. For game developers, contracts with publishers are one of

their key business relationships. The publisher typically provides not only

services and knowhow in marketing and distribution of games, but also serves as

a fundamental source for financing game development.

So as a developer, it is vital to consider the nature of cooperation with a publisher, and first and foremost what to pay attention to when negotiating the contract with the publisher.

First question: What do we need a

publisher for?

Any developer, but particularly one

negotiating a contract with a publisher for the first time, should ask

themselves at the beginning what they expect from their publisher, and then

consider what the publisher will expect of them.

In simple terms, the publisher’s role

boils down to three aspects:

- Financing production of the game

- Providing marketing of the game

- Organising distribution of the game and managing relations with distributors.

In practice, not all of these elements

will necessarily be involved. Contracts are often concluded where the publisher

does not finance development of the game, but handles solely distribution. There

are contracts where the developer assumes the responsibility for marketing and

does not expect any support in this respect from the publisher. But a classic

or full-service publishing contract will cover all three of these elements.

The publisher in turn expects the

developer to be in a position to create a work within a short timeframe in the

form of a game suitable for commercialisation and offering prospects for good

profits. Indirectly, the publisher also expects the developer to possess a

qualified team of people allowing the developer to meet this goal. In exchange

for its services—particularly when it also finances production of the game—the publisher

also expects a fee, typically taking the form of a defined percentage of the revenue

from sale of the game.

These mutual expectations point to the

fundamental areas typically addressed in the publishing contract, namely:

- Copyright to the game under development and other intellectual property rights

- The publisher’s rights and obligations with respect to distribution of the game

- Rules for financing production of the game and subsequent division of the profits from sale of the game

- The scope and nature of marketing services provided by the publisher.

In this article we focus on two of the

most fundamental issues, namely intellectual property rights and financial

aspects.

Intellectual property: As the developer,

can we retain the copyright to our game?

In the case of many developers

cooperating with a publisher for the first time, their first question is how concluding

a contract with a publisher will affect their copyright to the game they have

created.

In the past, publishers most often

expected the developers to transfer their economic copyright to the game to the

publisher to the fullest possible extent—particularly in instances where the

publisher agreed to finance production of the game. The practice today is

different, but as a developer it is still worth closely examining the

provisions of the contract governing the issue of intellectual property rights.

Now it is much more common in publication

agreements to regulate the publisher’s rights to use the video game (or rather

to exploit the bundle of various intellectual property rights involving the

game) through the grant of a licence. Thus this is generally a form that is

more limited. Nonetheless, publishers often expect the scope of the licence to

the IP rights granted them in the contract to be broad, a solution in practice

sometimes bordering on a transfer of copyright. It should be examined from the

developer’s perspective whether the scope of the licence demanded is truly

justified.

Scope of licence granted to the

publisher

In terms of the scope of the licence,

the following basic issues should be borne in mind:

- Territorial scope (i.e. in what countries the publisher obtains the right to exploit and benefit from the game)

- The platforms on which the publisher will have a right to commercialise the game (whether the publisher will be able to market the game exclusively in box form, e.g. at brick-and-mortar stores, or via certain digital distribution channels like Steam or the Epic Games Store)

- Whether the publisher will have a right to “port” the game to other platforms, and if so which (e.g. in the case of a game developed exclusively for PC, will the publisher also have a right to exploit and benefit from a new version of the game for consoles like PlayStation or Nintendo Switch)

- The right to localisation of the game, i.e. to adapt the language and narrative to make it relevant for users speaking other languages or coming from other cultures.

It should also be considered whether the

contract covers derivative works, such as sequels/prequels and merchandise

inspired by the game (shirts, toys etc). Sometimes these items can generate

significant revenue.

The licence may be exclusive or

non-exclusive. The first solution can be disadvantageous for the developer if

the developer is considering potential cooperation with other publishers as

well, who in certain aspects (e.g. in certain countries) have greater

experience in marketing or distribution or can offer better financial terms.

The period for which the licence is granted

must also be considered. Various solutions may be applied in this respect, but

publishers from the US or the UK often propose clauses defining the licence as

“perpetual.” Such clauses should be consulted with a lawyer specialising in the

law of the jurisdiction governing the contract, as copyright law does not

always allow the grant of a “perpetual” or “irrevocable” licence (more about perpetual

licences here).

The scope of the licence is vitally

important in terms of the overall contract and not only in the context of

intellectual property rights. The provisions governing the scope of the licence

usually also define the scope of the publisher’s obligations in the area of

distribution of the game, as well as the sources of revenue that will be

subject to division between the developer and the publisher as part of the

publisher’s fee—more on this topic below.

Finances: Will we receive funding from

the publisher to develop the game, and if so, will we have to pay it back?

The second key issue in game publication

contracts, from the perspective of both the developer and the publisher, is

finances. One of the publisher’s roles is often (but not always) to provide the

financing the developer needs to produce the game. This typically takes the form

of debt financing, i.e. an interest-free loan subject to repayment out of the

revenue from sales of the game.

Apart from the total amount of the

financing the publisher is willing to offer (which itself is obviously crucial,

as the amount must suffice to cover the production costs of the game), the

mechanism for paying out the funding also looms large. Most often funding is

provided by the publisher in the form of advances, released gradually upon

achievement of certain milestones in the game development process (e.g.

drafting of the game design document, completion of a prototype, preparing

a vertical slice). Thus the developer should first examine the description of

the milestones proposed by the publisher and the deadlines for achieving them. Situations

should be avoided where the amount of individual advances is insufficient to cover

the costs that will have to be incurred to meet the specific milestones, or where

the gap between advances is too long and could disrupt the development process.

It is also worth the effort to precisely

define the procedure for acceptance of individual stages. The developer should

focus on negotiating solutions such as:

- A set period in which the publisher must accept or reject each phase of development

- An obligation for the publisher to provide a detailed justification as grounds for refusing to accept a phase of the work

- Provisions under which the publisher is deemed to accept the phase of work if it fails to express a position on the work by the stated deadline.

It is also recommended that from the time

of approval of each phase, the publisher be required to pay out the next

advance of funding within a relatively short time. This precise regulation of

acceptance of phases and milestones helps avoid many difficulties during the

course of game development.

As the publisher is providing debt

financing, the provisions of the publishing contract on repayment of the

financing are also crucial. As mentioned, the financing is subject to repayment

out of the future revenue from game sales, referred to as the “recoup.” In

practice, publishers typically expect repayment of the financing to take total priority

over the developer’s benefit from sales. In other words, the publisher expects

the monthly sales revenue from the moment of launch of the game to be applied

first toward reimbursement of the financing, until the outstanding amount is

entirely paid down, and only after that point will revenue begin to be split

between the developer and the publisher in the defined proportions (more on

this below in the discussions of the publisher’s fee). This approach to repayment

of financing is referred to as a 100% recoup, as reimbursement of 100% of the

financing takes precedence over the normal division of profits from sales. But

sometimes publishers will agree to a lower degree of recoup, even 50%, particularly

in the case of developers with a certain reputation on the market. It’s worth

trying to negotiate such a solution, as it allows the developer to start

drawing profits from its game earlier. A solution involving a rate of recoup

below 100% is particularly important considering that most often the greatest

revenue from sales of a new game is achieved immediately following its launch. Thus,

in absolute terms, even a relatively small percentage of the revenue in the

first months can be significant.

Publisher’s fee for services: rules for allocation

of profits from the game

Apart from the publisher’s expectation

of repayment of financing provided for production of the game, it is also

natural for the publisher to expect a fee for the services it provides. The

publisher will most often collect this fee in the form of a set percentage of

the revenue from sale of the game after the advances for funding the production

are recouped. In practice, the division of revenue can differ greatly depending

on numerous factors, but it is not unusual to encounter a 20:80 split, where

20% goes to the publisher and 80% to the developer.

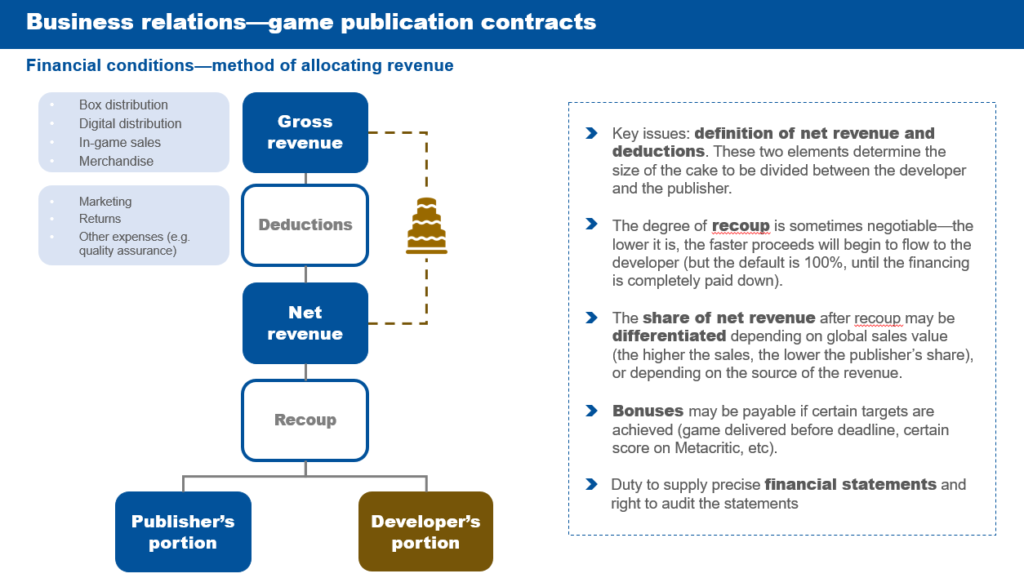

In this context, how the revenues

subject to division between the developer and the publisher are defined in the

contract becomes vital. Often the definitions prove more important than the split

as such. How the notions of “gross revenue” and “net revenue” are defined in

the contract deserve particular attention.

Gross revenue typically means all

sources of revenue counted for division between the publisher and the developer

(e.g. revenue from certain digital distribution platforms, revenue from “box”

distribution, revenue from “merch” and in-game sales, e.g. extra items used in

the game).

The second notion, net revenue, is

equally important if not more so. It captures the value of revenue subject to

division between the parties in the defined proportions after making certain

deductions from the gross revenue of expenses defined in the contract. Publishers

often expect that costs, e.g. for conducting marketing campaigns for the game,

will ultimately be borne by the developer, which in practice means that they

are deducted from the revenue generated from sales of the game prior to the split

according to the defined proportions. Net revenue also often reflects other

types of deductions, such as the value of returns by customers and other types

of expenses which the parties agree will be charged to the developer, e.g. the

costs of the quality assurance process preceding launch of the game on certain

platforms.

The connections between concepts like

recoup, gross revenue and net revenue are depicted in the diagram below:

The definitions of gross revenue and net

revenue in some sense define the size of the cake to be sliced up between the

publisher and the developer. Optimal definition of these terms often outweighs

the mere negotiation of a nominally preferential split.

In practice, particularly in the case of

games where the publisher is responsible for relations with distributors, profit

from sale of the game and other sources of revenue will flow first to the

publisher and later be shared with the developer. Thus the provisions of the

contract governing the publisher’s duties to accurately and regularly inform

the developer of the current financial situation related to sales assume great

importance. The standard in publishing agreements is a duty on the publisher’s

part to submit a detailed financial report to the developer each month after

launch of the game. The contents of the report are defined in the contract and typically

include information on the value of revenue in the given month from particular

sources (platforms, merchandise and in-game sales), the value of

deductions (e.g. for returns), the net revenue, and the developer’s and

publisher’s shares. In situations where the revenue from the game flows to the publisher,

there is a great asymmetry of information between publisher and developer. In

this case, the reports are an essential tool to ensure transparency of the

entire process of splitting the profit. From the developer’s point of view, it

is also worth negotiating a right to audit the reports by comparing them to the

source documents, which encourages the publisher to prepare them scrupulously. Moreover,

timely submission of reports by the publisher is vital from the developer’s

perspective, as typically the profits are split in the agreed proportions a

certain time after the publisher submits the report to the developer.

Other issues: exit plan, governing

law, and dispute resolution

Finally, the provisions governing the

end of cooperation with the publisher should be considered. Often one of the

foundations of good contractual relations is the knowledge that at any time

either party has a realistic possibility of walking away when this proves

necessary for legitimate reasons.

In this context it should be examined

whether the contract contains any grounds at all for termination or repudiation

by the developer. Sometimes publishing contracts contain only provisions giving

the publisher rights to unilaterally terminate the parties’ cooperation. By

contrast, examples of grounds for unilateral termination by the developer might

include situations such as:

- Publisher’s

delay in payment of advances exceeding a set number of days - Publisher’s

delay in launching sales of the game within a certain period after the

developer’s delivery of the “gold master” version of the game ready for

commercialisation - Publisher’s

delay in submitting monthly financial reports on game sales.

Apart from a reasonable definition of

the grounds for terminating the contract, it is key to include an exit plan in

the contract, i.e. to expressly address the results of termination of the

contract during the course of performance, in terms of intellectual property

rights, repayment of financing, and division of revenues. Only with a properly

defined exit plan can the parties realistically consider exercising their

rights to unilaterally terminate the contract. Otherwise, these rights may

prove illusory, as exercising them will carry too great a risk of uncertainty about

the consequences.

Apart from the issue of contract

termination, it is essential to examine which jurisdiction’s laws govern the

contract. This issue is usually addressed near the end of the contract in a

choice-of-law clause stating that the contract is concluded for example under

Polish law, English law, or the law of some other jurisdiction. This is an

issue of fundamental importance.

The dispute resolution clause is another

important provision, specifying which authority will be competent to resolve misunderstandings

that may arise between the parties—whether the state courts of a given country

or an arbitration court—or requiring the parties to resort to mediation.

Summary and general remarks

A developer negotiating a contract with

a publisher must consider many essential issues. Some of the most important

provisions are those governing intellectual property rights, financing of game

production and repayment of financing, and division of profits from sales

between the publisher and the developer. But the issues touched on in this

article are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the matters typically

covered by a game publishing contract.

A developer negotiating the contract itself

must remember several fundamental principles. First and foremost is to clarify

with the publisher (which most often proposes the first draft of the contract

as a starting point) the meaning of any provision the developer does not

understand. It is also vital to try to ensure that the explanation provided by

the publisher on the meaning of particular provisions is ultimately reflected

in the wording of the contract. Even if not every aspect of the contract can be

negotiated, it should certainly be clear to both parties, and there is no

reason the publisher should not agree to explain what the provision means.

The tunnel thinking syndrome must also

be avoided. Sometimes it is not worthwhile to focus all the party’s efforts on

negotiating an advantageous wording of one provision that seems crucial (such

as the split of profits from the game). It is preferable to look at the contract

as a whole and focus on negotiating several advantageous changes instead of one

that is particularly difficult for the parties.

Considering how specific and complicated

game publishing contracts can be, it is also worth consulting the draft with a

specialist, and if possible entrusting to them the entire negotiation process. Ultimately

this is the key contract on which the success of the game may depend.

Jakub Barański, New Technologies practice, Wardyński &

Partners