Dematerialisation of securities in Poland: Chaos or a brilliant plan?

Across all fields of life we witness groundbreaking changes brought by new technologies. Progressive digitalisation is not sparing the financial markets, which are indeed perceived as an area that will be shifted almost entirely into the digital world. The goods traded on financial markets rarely take material form, but are typically some type of abstract right.

The basic and most obvious challenge for digitalisation of financial markets is to eliminate paper where entries in IT systems prove to work better. Traditionally and historically, securities have taken paper form, but that clearly does not meet the requirements of contemporary trading on financial markets studded with state-of-the-art technologies.

Stripping

securities of their traditional paper medium has come to be called

“dematerialisation”—in a general sense, as in Poland this concept mainly

functions in a narrower legal meaning referring to situations where securities

are dematerialised using a central depository. In this sense, dematerialisation

does not necessarily mean digitalisation of the security instruments as such.

In a certain classic sense, a form of dematerialisation could be replacement of

a documentary security with a book entry, which could function in a digital

record but also as a notation in a traditional ledger. In this context we

should mention “immobilisation,” which in certain jurisdictions serves as the

basis for shifting securities and trading into the digital world without eliminating

the strict legal connection between the security instrument and its paper

medium, but enables trading in rights to securities in such a manner that in

practice the paper medium becomes a mere formality.

New regulations on dematerialisation

Recently we have

observed in Poland an onslaught of regulations directly or at least indirectly connected

with the broad issue of dematerialisation of securities. These include:

- Now-mandatory regulations on dematerialisation of

bonds - Regulations on dematerialisation of stock in

non-public companies - Regulations governing the simple stock company.

On top of these

we should add the regime of dematerialisation functioning for years under the

Trading in Financial Instruments Act, primarily governing securities that are

the subject of organised trading (i.e. on the regulated market or in an

alternative trading system).

It seems that the

trend toward dematerialisation of securities in this or some other form is an irreversible

element of ceaseless technological development. Thus the prospect of a future

in which securities are universally held in dematerialised form appears likely.

But to take full advantage of the benefits of dematerialisation requires

adoption of rules forming a coherent system, able to handle further

technological changes no doubt awaiting us.

What sort of dematerialisation do we want?

Logic would

dictate that all regimes for dematerialisation of securities in Poland should

remain mutually consistent. Although there are sometimes far-reaching

differences between certain types of securities, securities represent a fairly

consistent legal institution which should be governed as far as possible by a

comprehensive set of standards. This should not prevent differentiation between

securities (stocks, bonds etc), while securities as such constitute a separate

and recognised legal institution with certain fixed, characteristic features. Thus

it would appear optimal to refer to a universal system of

dematerialisation shared as a rule by all securities.

It must also be

borne in mind that dematerialisation is a product of trends in technological

change. But technology will continue to evolve. For this reason, any efforts to

create a framework for dematerialisation of securities should place a serious

emphasis on ensuring technological neutrality. We wouldn’t want to find

ourselves in a situation where after conducting a complicated process of dematerialisation,

we would shortly have to conduct another “de-” process to bring our already dematerialised

securities into compliance with another form and state acceptable under some

new technological reality. In other words, dematerialisation should be a

universal process, allowing securities to function in a digital reality

regardless of the specific technology currently being used—much as traditional

paper securities existed and served commerce well for hundreds of years even as

radical changes occurred in the underlying economic realities.

Do we now have the sort of dematerialisation that we want?

Until recently,

dematerialisation primarily involved securities subject to organised trading

(on the regulated market or in an alternative trading system). The Trading in

Financial Instruments Act defines dematerialisation as the absence of document

form of a security from the time it is registered pursuant to a contract on

registration of securities in the securities depository. Dematerialisation defined

in this way (which we may refer to as dematerialisation in the strict sense)

thus involves exclusively securities that do not have a documentary form and

are subject to registration in the securities depository. Eliminating the form

of a document from securities in some manner other than registration in the

securities depository may thus be defined as dematerialisation in the broader

sense.

By the way, we

should also note the broad definition of “document” in the Civil Code (“a

carrier of information enabling knowledge of its contents”), which in the context

of the regulations on offering and trading of securities sometimes sows

confusion, particularly among non-lawyers. It should be acknowledged that the references

to the term “document” in the regulations governing securities often do not carry

the Civil Code meaning, but simply refer to “paper” form.

The earlier,

relatively narrow dematerialisation regime in Poland seemed logical, as

dematerialisation is particularly useful in the case of public trading in

securities. But in recent years it was decided to take steps toward

dematerialisation of types of securities that are not the subject of organised

trading. This refers to “private” bonds, stock in non-public companies, and

shares in simple stock companies.

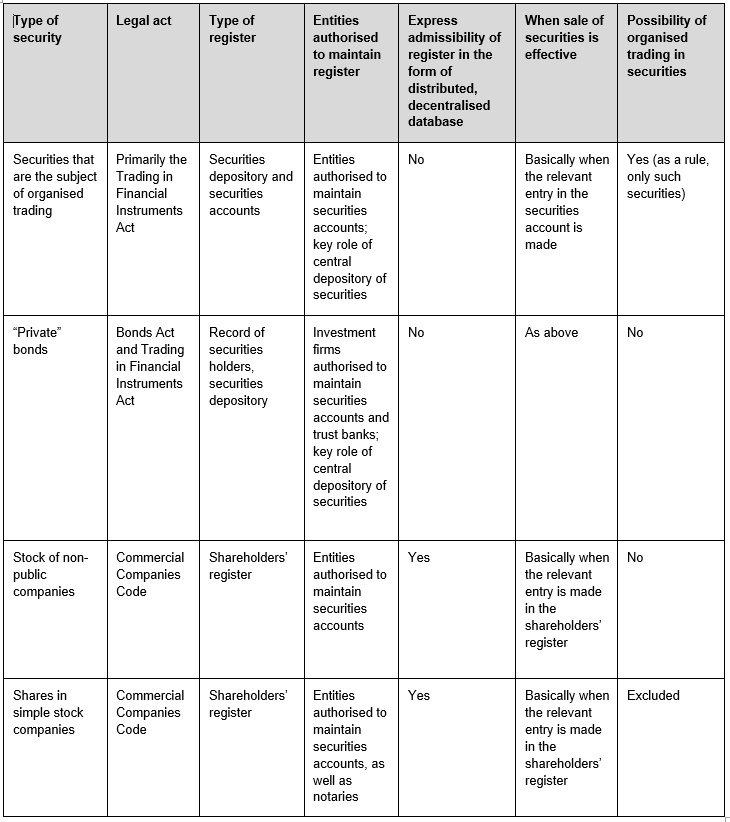

The chart below depicts the existing (or soon to be introduced) regimes for dematerialisation of these types of securities:

As is apparent,

there are significant differences between the specific regimes for

dematerialisation of securities. But they are partially compatible with one

another, particularly in the case of non-public companies and simple stock

companies, where the terminology and wording of the provisions were unified

during the legislative process. It seems that the system for dematerialisation of

securities in Poland could benefit from further convergence in these systems. At

the same time, legitimate differences could be taken into account, e.g. between

securities that are or are not subject to organised trading.

The greatest

challenge remains how to frame the system for dematerialisation of securities

so that it can successfully rise to the challenges presented by further growth

in new technologies. This is particularly relevant in connection with the

“tokenisation” of assets and the use of blockchain technology. These methods raise

particular questions concerning the methodology of dematerialisation based on book

entries, requiring the involvement of an entity maintaining the ledger. Some

crypto-assets display more of the features of bearer assets, which are not in the nature of abstract rights

but rather suggest things covered by absolute subjective rights.

The need for a discussion of reform of Polish securities law (civil and regulatory) is becoming increasingly pressing, in order to meet the requirements of contemporary commerce. But what is surely not called for is more incremental, discrete changes in the legal system, which would further complicate the already highly complex legal framework for dematerialisation.

Jacek Czarnecki